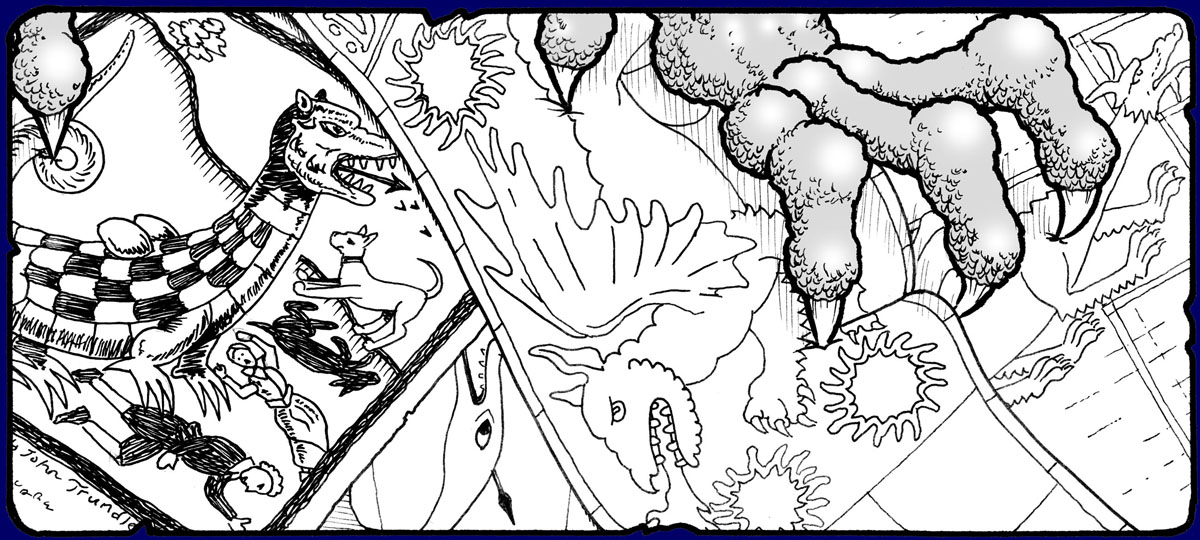

|  | |  | |  | | Everybody seems to know what a dragon is nowadays; they feature heavily in stories, movies, TV, and games, and are usually portrayed as giant, lizard-like creatures with long necks and tails, horns, leathery wings, and generally belching fire from their nostrils and mouths. Further, its often asserted that tales of dragons go far back into history, showing these creatures are deeply rooted in many cultures with many different types; and that the original ideas regarding dragons may have derived from ancient explanations of dinosaur fossils.

All of which looks like it might be wrong...| MH&T is supported by its Patrons!Click Here to go to Full Article in Patreon Monsters Here & There and its sister site Anomalies are supported by my Patrons, people like you. Part of how I thank them is to present articles that only they get to see, and this is one of them. The full article is available at the Patreon website. You can become a Patron by making a recurring pledge of just $1 a month! All Patrons get early access to all new articles for both websites as well as, of course, exclusive articles and other extras! So help me explore the world of creepy and cool creatures, while giving yourself access to even more great stories! Learn More about Becoming a Patron at Patreon |

| |  | |  |

|