| Area(s) Reported: Turkey or Africa

Date(s) Reported: Previous to 303CE

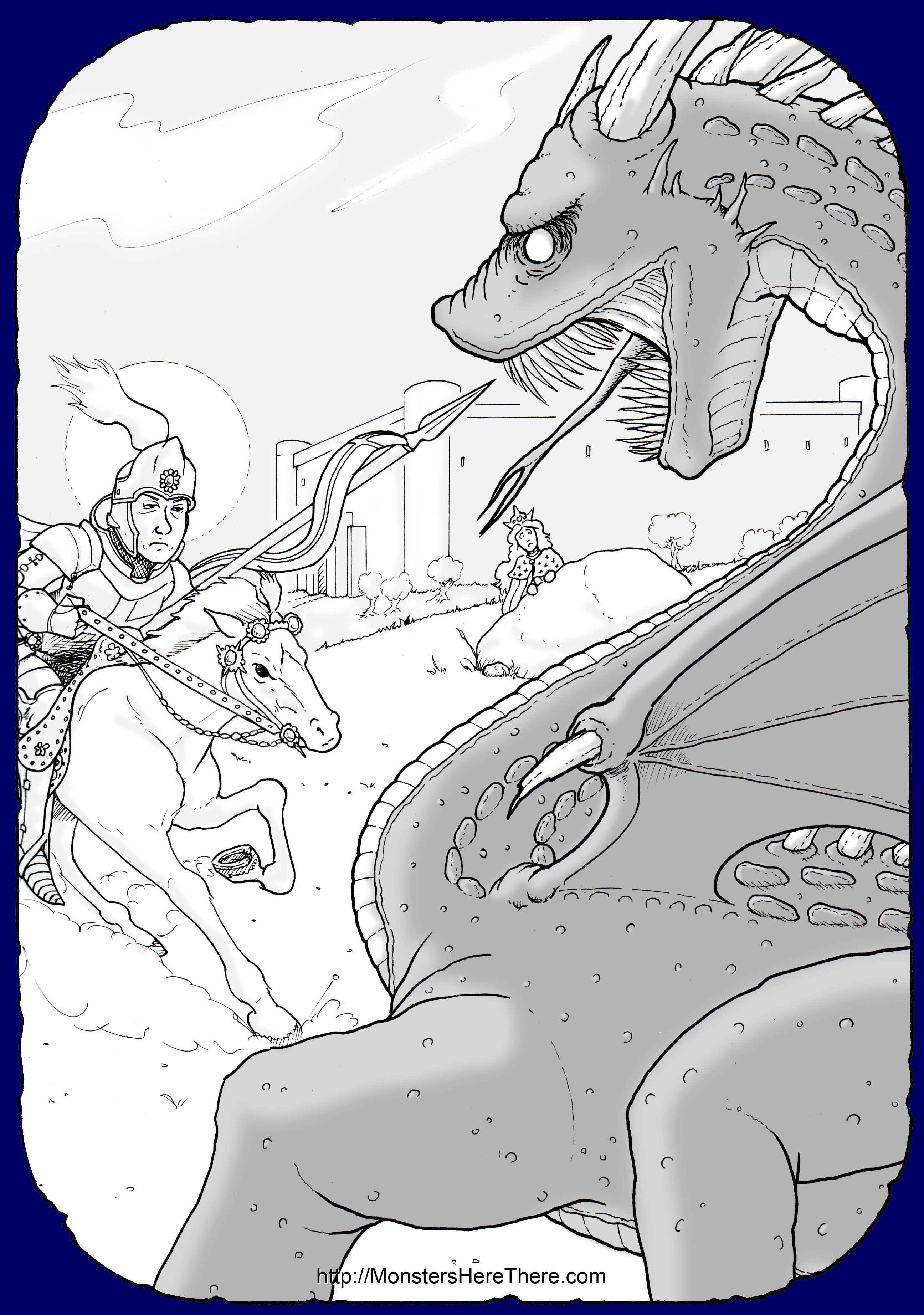

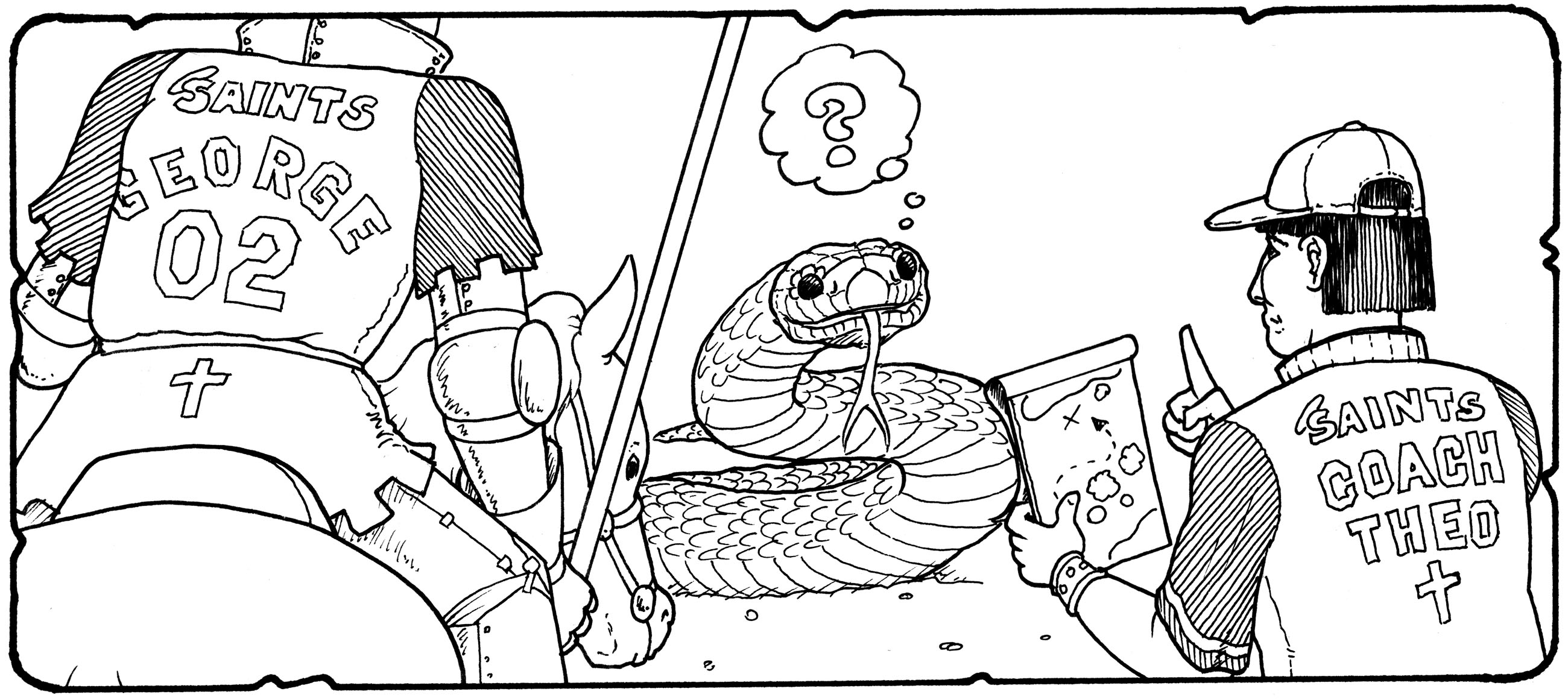

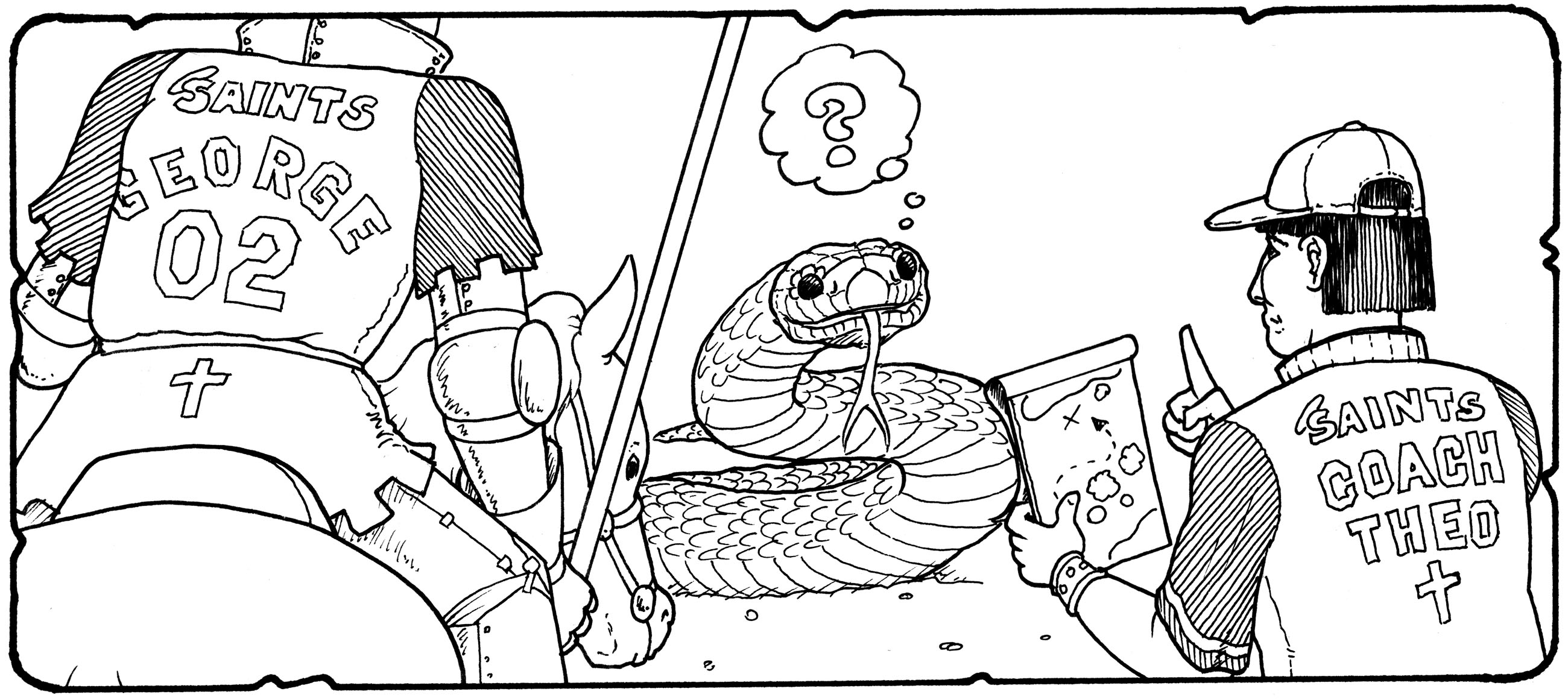

In Europe, dragons often appear in stories as an evil monster that must be defeated to make peoples' lives better. These moral tales are what largely form the current idea of dragons, and the most influential of these tales is that of 'St. George and the Dragon.' Historically speaking, not a lot is known about St. George. It's believed he lived in the 3rd Century, and died on April 23, in 303CE. He was a soldier for the Roman emperor Diocletian at the time of his death, and he was killed because he would not renounce his Christian faith... and this willingness to die for his beliefs soon saw him recognized by other Christians as a martyr, and later declared a Christian saint. Saints are a sort of good monster, by the way; they are people who have died, but can return to Earth to perform great deeds and miracles to help the living. Perhaps not surprisingly, St. George has been a popular Christian saint for soldiers, since George had been one himself during life. The events of our tale, however, occurred before George died and was declared a saint; so, technically, it should be known as 'George and the Dragon'... but let's just let that one go. According to a copy of the legend published in 1633, a city called Silena in Lybia, Africa, had its water supply, a large lake, inhabited by a dragon. The dragon would sometimes come near to the walls surrounding the town, and its poisonous breath would cause the people of the town to become sick and, in some cases, die. Looking for some sort of solution, the residents of the town discovered that if they left two sheep out by the lake for the beast to eat each day, the creature would stay away from Silena itself. But this went on so long that the supply of sheep dwindled... and when they could no longer supply two sheep, the town was forced instead to sacrifice one sheep and one person... and, generally, a child. We are not told how the city selected their victims for this sad task; but one day this unspecified selection fell upon the king's daughter, the young princess of the town. Though both the king and queen tried to spare their daughter the cruel fate, the townspeople were not so accommodating... especially those who had already lost children to the monster. And so the young princess was taken to the fields, stripped of her fine clothing, and chained in preparation for her sacrifice. Luckily for the princess, George was riding through the area at the time and -- like any helpful hero would -- immediately asked what was going on. Unchained, the young princess explained the whole dreadful problem to the soldier, and George decided on the spot that he must try to stop the dragon and end the need for children to die and the town to suffer. We are told it was a fierce battle between the soldier and the dragon -- though no real details are offered up -- but George managed to strike a fatal blow, which is typically shown in artistic representations as George spearing the monster from horseback. Afterwards, we are told, the King of Silena was so impressed with the good soldier that he willingly chose to convert to the Christian religion, and soon all of Silena became a town of devout Christians, just as their savior was. The Tale of the Tale The first questions that tend to come up at this point are a little opposite each other: at one end I hear people asking "what did the dragon look like?," and at the other end I hear "did it really happen?" Don't worry; I'll cover both! The tale as told in the 1633 document doesn't actually describe the dragon at all; but I can make a pretty good guess. The earliest reports regarding 'draconem' -- what would later be called "dragons" -- were nothing more than giant snakes. Draconem were considered to be the king of the serpents due to their enormous size; and that St. George's dragon was considered to be a gigantic serpent is shown by a 10th Century illustration of both St. George and St. Theodore (more on him in a moment) slaying a snake bigger than their horses. But there's one other good reason to suspect St. George's dragon was considered a gigantic snake: in Biblical religions, snakes were considered to be both agents and symbols of evil, and dragons -- being the largest of snakes -- were considered to be symbolic of the greatest evil, a being called the Devil. So with this in mind, a saint defeating a dragon is symbolically the same as that saint defeating the Devil, and therefore the foundation of evil... which is about the most heroic thing a saint could be said to do! Modern depictions of St. George's dragon tend to look more like modern ideas of a dragon; wings, legs, often breathing fire. This image of George's dragon changed over the years as the general idea for dragons changed... but the original beast was a monstrous snake with poisonous breath, a feature that was once common in dragons. Which brings me to the next question: "Did it really happen?" Ahem... NO. As a matter of fact, the original tale wasn't even about St. George! It was, in fact, a tale attributed to a number of different saints before George; but mostly to that 'St. Theodore' I mentioned a moment ago. St. Theodore of Amasea died in the early 4th Century, and is said to have been a soldier... but almost everything past that is legend, including his involvement with the dragon. In the 10th Century, there appears to have been a coordinated effort on the part of the Christian religious authorities to shift the story of the dragon slaying to St. George. If I had to guess why -- and I just have to -- the overall story was considered a useful inspiration for soldiers being encouraged to go out and slay 'evil' (in the form of religious enemies), and the people telling the story wanted the lead hero to be a soldier/saint that was better known and more popular than St. Theodore was. George was already considered to be the patron saint of soldiers... so he was an easy pick!

So, between the 9th and 11th Centuries, artwork appears that shows both St. George and St. Theodorus fighting the dragon, usually with George's spear in it and Theodorus playing cheerleader. By the late 11th Century, St. Theodorus was dropped from the art as well as from the story, and it was all George from then on. In the twelfth century, the whole story went the medieval equivalent of 'viral,' spreading across Europe and Asia into many, many languages, becoming a staple of not just Christian storytelling, but of other cultures as well (with a few changes). It's a fair bet that the tale of 'St. George and the Dragon' is the starting point now for almost all stories where a knight saves a maiden from a dragon, with one big exception... George was never interested in the princess romantically.

See also: The Devil & his Demons | |