| Area(s) Reported: Europe & North America

Date(s) Reported: about 1871 to Present

"The rosy clouds float overhead,

The sun is going down;

And now the sandman's gentle tread

Comes stealing through the town.

'White sand, white sand,' he softly cries,

And as he shakes his hand,

Straightway there lies on babies' eyes

His gift of shining sand." -- from "The Sandman" by Margaret Vandegrift, 1890 |

The Sandman is said to be a little man who visits children and uses magic sand to lull them to sleep and give them wonderful dreams. This is said to be why children sometimes wake with “sand” in the corners of their eyes... it's just the leftover dust dropped by the Sandman! The initial simple idea of the Sandman seems to have first appeared in Germany. A German/French dictionary published in 1771 explained that the German idiom "der Sandmann kommt" -- "the Sandman comes" -- meant that a person looked as if they would soon be asleep. In a 1798 German grammar dictionary the same idiom is described as a humorous thing adults say to a child when they rub their eyes as they get sleepy, implying they were rubbing their eyes because the Sandman's sand had just been sprinkled into them. While it's anyone's guess as to how long the joke about the Sandman existed previous to 1771, to become an idiom in a language proves a phrase has very common use; so it's likely the simple Sandman joke had been around for quite a while in German culture before 1771. A Scary Variation In 1817, a German author known as E.T.A. Hoffmann [1776-1822] wrote a short story entitled "Der Sandmann"... "The Sandman." The story is an intriguing blend of science fiction and fantasy which begins with the lead character describing an odd set of events from his childhood, which included his nurse telling him a terrifying story about a "Sandman" who throws sand in children's eyes to make them fall out, and then feeds these to his own children on the dark side of the moon.

This oddly threatening story is reinforced shortly after when a strange man who secretly visits the boy's father each night threatens to cut the young boy's eyes out for daring to peek in on the visit; instead, the man beats the boy soundly after the boy's father begs him not to blind the boy. Days later, the boy's father is killed in an explosion during one of these secret nightly meetings, and the threatening man disappears. The real story is now introduced: the lead character is now grown up, and believes he has once again encountered the threatening man who he believes killed his father... and Hoffmann's story itself never comes back to the topic of the Sandman legend which, in context, could be seen as the nurse warning the boy to stay out of the way. Hoffmann's story was a one-off use of the Sandman that German readers all would have recognized as a just an inventive use of a going idea. But overall Hoffmann's "Der Sandmann" was also a very good story, which was noticed by other Europeans. In 1834, Hoffmann's story was translated to English and included in an annual gift magazine called The Keepsake, which was a yearly compilation of fine art and good literature intended to be given as a gift around Christmas time each year in England. Though Hoffmann's story was strange and scary, this was a time in England when ghost stories were still told as part of Christmas festivities... so this creepy tale fit right in! It seems likely that someone went back to ask about the original German idea of the Sandman after this publication happened... because that would help to explain what happened next. Improving on Perfection

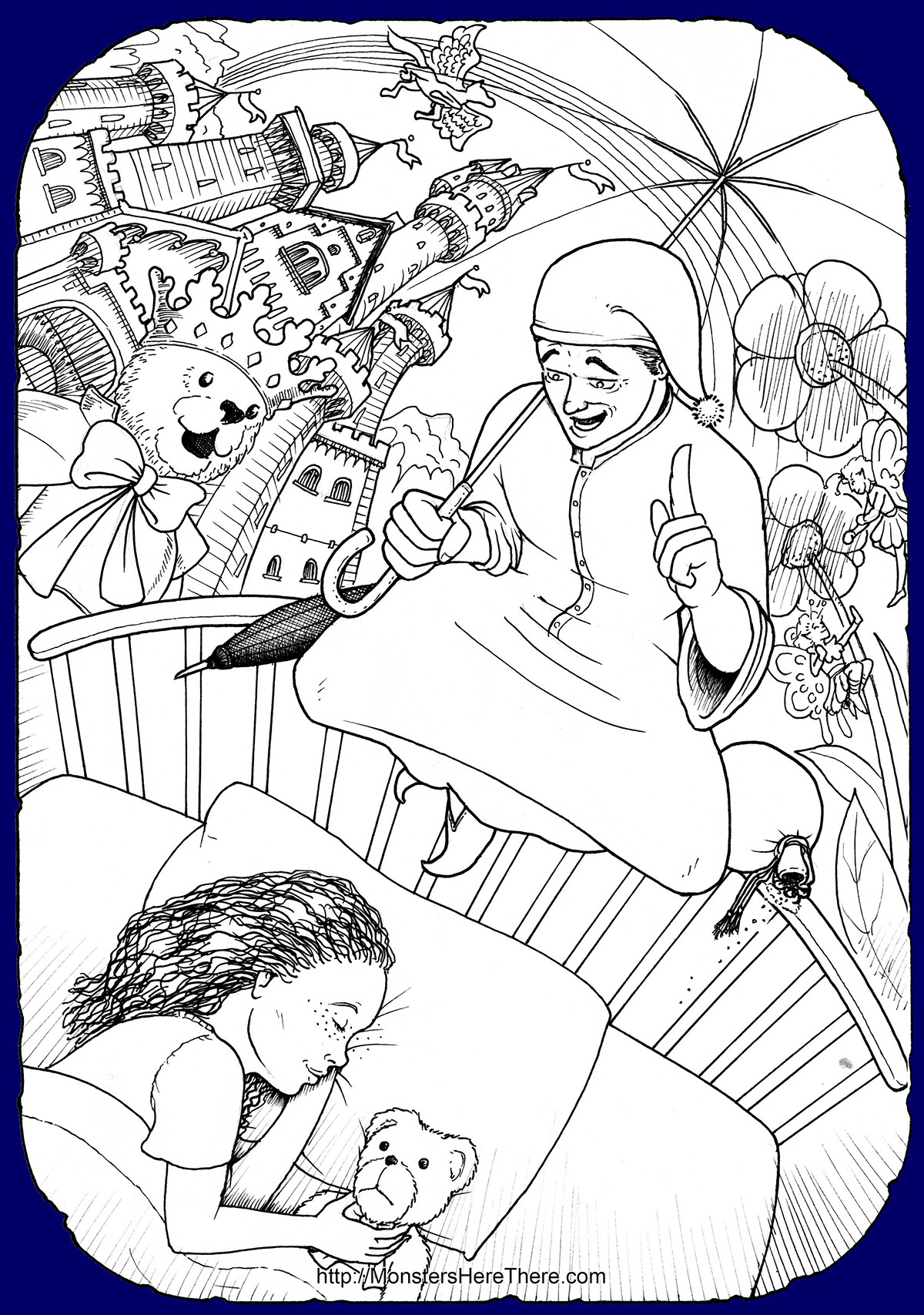

In 1841, Hans Christian Anderson [1805-1875] published one of the collections of fairy tales that he eventually became famous for; this collection in particular included a story called "Ole Lukøie" which was about a little man in nightclothes (pajamas) who used magic umbrellas to bring good dreams to good kids, and dreamless nights to bad kids. The name Ole Lukøie roughly translates as 'Mr. Shut-Eye,' which makes sense since he first coaxes children to sleep so he can tell them tales... but something interesting happened when this fairy tale was translated to English. In the first English translation of Andersen story in 1846, we're told how 'Ole Luckoie' (an easier name for English speakers) would, among other things, flick sweet milk into children's eyes so they would start to shut them and not see him... which agrees with Andersen's original tale. In 1852, however, two different new translations of the story changed the detail about the sweet milk to be "a certain powder" in one and "dust" in the other... and one of the two directly mentions the German idea of the Sandman in a footnote to the story. By 1861, new translations of the story simply renamed the character to be "The Sandman" instead of "Ole Luckoie," and so the old German Idea was assigned a whole new life in English literature. It didn't last too long, though. The Benevolence of the Sandman Aside from the altered version of Andersen's fairy tale, the Sandman often got brief mention in new stories and poems; and in these, a new story slowly evolved for the bringer of dreams. By the 1890's, new poems about the Sandman paint a slightly different character. Still envisioned as a small man (or sometimes a child) in nightclothes, gone are Andersen's magic umbrellas, replaced purely by bags of sand that bring sleep and dreams and, occasionally, a bag of sand that brings only sleep... but mentions of the Sandman's intention to punish children were no longer stressed over the rewards of wonderful dreams for good children. Some poems also celebrated the gift of sleep from a parent's point of view; without the Sandman, how would a fussy baby calm down?

Stress was also placed upon the Sandman's astounding ability to tell stories -- since that's what dreams were said to be -- and the early part of the 20th century saw the publication of many children's books attributed to the Sandman as the author, much as the fictional "Mother Goose" had been credited with anonymous nursery rhymes. Since then, the Sandman has become presented as a sort of fairy-like being who is only concerned with children's welfare... which, frankly, is not a bad thing to be known for! So be good, and earn those dreams; and please forgive the Sandman if, in his enthusiasm, he leaves a little extra sand in your eyes in the morning. | |